AGAVES

The agave is the most complex and interesting plant distilled by humans. All the intense energy and flavorful components built up in the 8 to 15 years it takes the plant to mature, meant to be used to grow that huge stalk and produce flowers – just before it dies – is instead concentrated and purified by distillation into the agave spirit: mezcal, raicilla, tequila.

Prehispanic indigenous peoples roasted the agave to eat, drank the sap (or let it ferment into pulque), used the thorns for needles, used the leaves for roofing, used the fibers for thread, cordage, and clothing.

Ansley Coale talks about mezcal and pulque here

So don’t talk to me about barley or corn or grapes. Mezcal fresh from the still is as complex and interesting and tasty as excellent brandies and whiskies after years of aging. At Germain- Robin, often called one of the world’s finest spirits, we made brandy from very good wine grapes, but they were all variants on one species, vitis vinifera: there was a stylistic uniformity.

Some 25 or 30 genetically different agaves can be distilled, some of them so rare that they have not been given scientific names, and the range of flavor, aroma, intensity is astonishing.

Agaves are their own scientific family. Close to 30 species are distilled in Mexico (we have two rare ones that are not on the standard list), and they grow in a wide variety of soils, at different altitudes, and in different microclimates, although all of them are tolerant of, and develop their best flavors, where it’s dry.

Apart from tequila, which by regulation uses the blue agave Weber, most agave spirits are distilled from cultivated espadín (agave angustifolia). Espadín develops a lot of local individuality not just from soils or microclimates, but from genetic changes over time asthey grow in the same area for centuries. Jalisco espadín is noticeably different from Oaxacan espadín. That’s why family distilleries can make such good stuff: they understand the local agaves.

Agaves propagate by rhizomes (plants growing out of the mother plant’s roots), by seeds, and by bulbuls, baby plants that grow out of the base of older agaves: the Mexicans call them hijuelos, little kids. People plant entire fields with transplanted hijuelos. The downside is lack of genetic diversity, especially in tequila plantations.

Agave seeds at Real Minera.

The most distinctive agaves are wild or semi-wild (wild ones propagated by hijuelos). In Miahuatlan they plant semi-wild madrecuishe along roads or to mark the edges of cultivated fields.

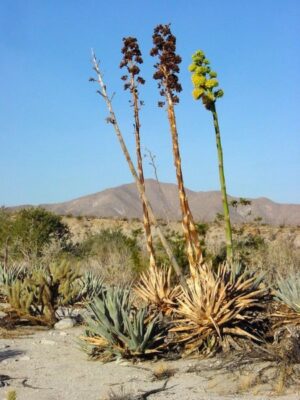

A lot of plants used for distillation produce their best stuff when they have to struggle: hillside vineyards, high mountain sugar cane (Dakabend rum), and especially wild agaves. Here’s a planting of struggling espadín.

Agaves untamed

Our favorite mezcals are wild tobalá (agave potatorum)(in photo), especially from the mountains around Sola de Vega, and wild jabali (agave Convallis), and

cupreata, which grows on steep high-mountain terrain, especially in Michoacan.

Wild tepextate (agave marmorata). These can weigh 150 lbs and take 15 years to mature

Wild rhodacantha (agave Mexicano). A favorite in Jalisco

The hypnotic symmetry of the agave

The tiny wild lechugilla, so rare that it has no scientific name. It can take up to 30 years to mature.

Huge agave salmiana starting to flower