A web journal about craft methods of distillation

Editors: Will Hodges & Ansley Coale

Cognac Potstill: the chapiteau

Cognac Potstill: the chapiteau

Why we use copper stills

Why we use copper stills

Making the Seconds cut/brandy run

Making the Seconds cut/brandy run

Measuring Brix

Measuring Brix

Using faibles

Using faibles

Making the heads cut/brandy run

Making the heads cut/brandy run

Assembling Germain-Robin XO

Assembling Germain-Robin XO

Grading new oak barrels

Grading new oak barrels

Still refurbished

Still refurbished

Here’s one pot broken out from its original masonry installation. You can see the line of the edge of the cement enclosure just below the line of rivets. At right, the drain. Note again the change in color where it exited the enclosure, showing the thickness of the insulation.

A close up of a preheater. On the near right side of it, the tubes and valves for a sight- glass. On the floor at left, the chapiteau (in bronze!) and swan’s neck. In the back right, the condenser tank.

You can see the top of the copper coil inside the condenser tank, left.The brass rings/handles on the sides are for hoisting.

The drain and valve on the 2nd pot.

Tasting Petite Champagne

Tasting Petite Champagne

MAISON SURRENNE COGNAC

MAISON SURRENNE COGNAC

Tasting Grande Champagne Cognac/Maison Surrenne

Tasting Grande Champagne Cognac/Maison Surrenne

Starting a distillation run

Starting a distillation run

How a double-distillation pot still works: basics

How a double-distillation pot still works: basics

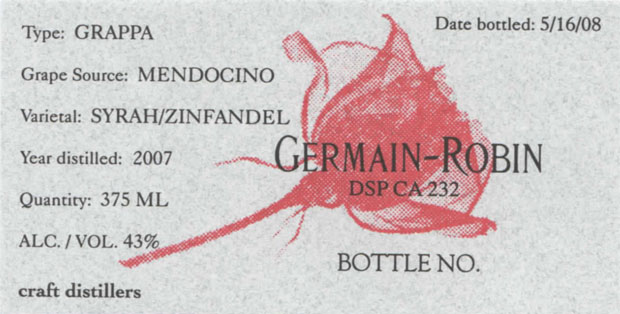

Grappa Label

Grappa Label

When I was posting the piece on grappa of viognier, someone asked me about the label. It’s a rose on its stem: beauty emerging from thorns the way grappa at its best is beauty distilled from left-overs. The image is actually an X-ray of a rose: stripped-down rose the way grappa is stripped-down grape/ansley coale

GERMAIN-ROBIN BRANDY

GERMAIN-ROBIN BRANDY

Germain-Robin Viognier Grappa

Germain-Robin Viognier Grappa

Recently I was out in the market with a stick-on labeled bottle of Germain-Robin Viognier grappa, stick-on because we had just bottled it and hadn’t gotten around to the hand-labeling. I received some pleasant words about its quality. Here’s why.

Traditionally, grappa is made using just the pomace, which is what’s left (the grapeskins, stems, and seeds), after you press the juice out of grapes. You add some sugar and water to this. The water is to pick up some of the residual flavor and make it possible to distill; the sugar is so there so that the pomace, when fermented, will contain enough alcohol for distillation. It used to be just a cheap way of making booze with leftovers. It can be pretty crude, especially if you let the pomace lie around for a couple of days, and a lot of people have had unpleasant experiences with grappa. In the late ’80′s, several quality Italian producers started using the entire grape, juice and pomace together, to make their grappa, and that is what Germain-Robin does. As a result, our grappa is noticeably brandy-like. We call the process “whole-berry.”

Germain-Robin makes grappa mostly for fun: one batch is about 90 gallons, about 75 cases of the 375ml bottle we put it in. This is really not a commercial amount, and we sell more than half of it out of the tasting room. The Germain-Robin distillers like to experiment. They don’t make the same grappas year after year. They’ve tried muscat, they’ve tried riesling, they’ve tried merlot, but their favorites are syrah, viognier, and zinfandel. This is the second time they’ve bottled viognier as a grappa.

The grapes for the grappas don’t always come from the same vineyards. We simply keep an eye open for a small quantity of likely grapes. As it turns out, only about one batch in three is good enough to stand on its own as a grappa. When a batch is not up to snuff, we age the distillate in oak as a brandy and use it for blending: a little extra complexity.

Viognier is an interesting grape. Wine made from viognier is beautifully aromatic (peaches!), and despite a somewhat undistinguished reputation can be surprisingly complex. Germain-Robin has found – from many years of distilling excellent varietal wine grapes – that the varietal characteristics that you notice in the wine come across very clearly when you use the wine for distilling: viognier brandy/grappa has beautiful peach aromatics. It’s also very soft in comparison to other distilled wine spirits: there’s very little sense of alcohol. This characteristic of viognier was the secret behind Hangar One straight vodka. The St. George distillers blended in a vodka made on a pot still from lees of viognier wine, and as a result, the vodka had none of that unpleasant ethanol vodka smell.

One of the viogniers G-R made for grappa was so good and so distinctive that we bottled it as one of our series of single-barrel varietal brandies. It was amazing, one of the best things we ever made. I have half a bottle at home, that’s it: came and went/ansley coale

New Tanks

New Tanks

The Germain-Robin distillery, which moved to Redwood Valley in 1999, recently installed four vertical stainless steel tanks aggregating 11,000 gallons.

Right now, the G-R distillery actually functions as two distilleries, operating under a space-sharing arrangement complying with complex governmental regulations for “Alternating Premises.” G-R, whose brandy license does not allow it to make whiskey, leases space and equipment to Crispin Cain’s Tamar Distillery, which has a license allowing production of all kinds of distilled spirits. This is where Crispin is distilling and aging Low Gap whiskey and distilling Russell Henry gin.

When Hubert and I were putting G-R together (starting in 1982), we didn’t have much money. We looked around for used stainless steel tanks, which are used to store distilling wine, heads and tails from the distillation run, and brandy when it is being readied for bottling. We found three used wine and dairy tanks, which we could use for storing distilling wine and tails, but thankfully somebody told us that the normal stainless steel these tanks were made of didn’t stand up to high alcohols. It turns out that, for brandy, we needed tanks made of a stainless steel called Type 316 (normal is Type 304), which is .03% molybdenum and less than .08% carbon. What this means in real life is that Type 316 resists corrosion. Strong alcohol is a very powerful solvent, and if you put brandy or whiskey in a standard Type 304 stainless wine tank, the spirit may pick up an undesirable metallic taste. Unfortunately for us, Type 316 costs more.

Coming back to this week, we were able to find two used Type 316 tanks in a pharmaceutical plant that was going out of business, so it wasn’t too bad of a hit. We were able to get a good price on the other two because of the recession.

Two of the tanks will be used by G-R for blending a pear liqueur and for stabilizing and filtering an expanded production of apple brandy (a new version, to be released in 2013, is based on heirloom cultivars). The two tanks in the background are leased to Tamar for fermenting beer to be distilled into Low Gap whiskey, and also for Crispin Cain’s gin project/ansley coale